HILDUA + QARTIMME

We arrive

at the fifth name in the list of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (676 BC) of the

towns of the kingdom

of Sidon MISSION

Han

al-Hulde.

Lipinski

states in his book Itineraria : “Here is

a general agreement in identifying Hi-il-du-u-a with the mutation Heldua of the

Bordeaux Itinerary and with present-day Halde,

known in earlier literature as Han al-Hulde, 12 km south of Beirut Beirut to Sidon

Lipinski is

right, that Han al-Hulde (south of Halde or Khaldé) is the Roman-Byzantine

town, but what is lying underneath it? Was that Hildua from the 7th

century BC, or just bare grounds? In any case, it is only sure, that Han

al-Hulde is at the first place a Roman-Byzantine town out of the late Roman

period, although there are some objects found out of the Persian and

Hellenistic period.

Because in

Han al-Hulde or in the vicinity are found graves and inscriptions:

RES 1916:

inscription with ink on an amphora founded in 1897. Text: ‘d’g‘lt. Meaning:?

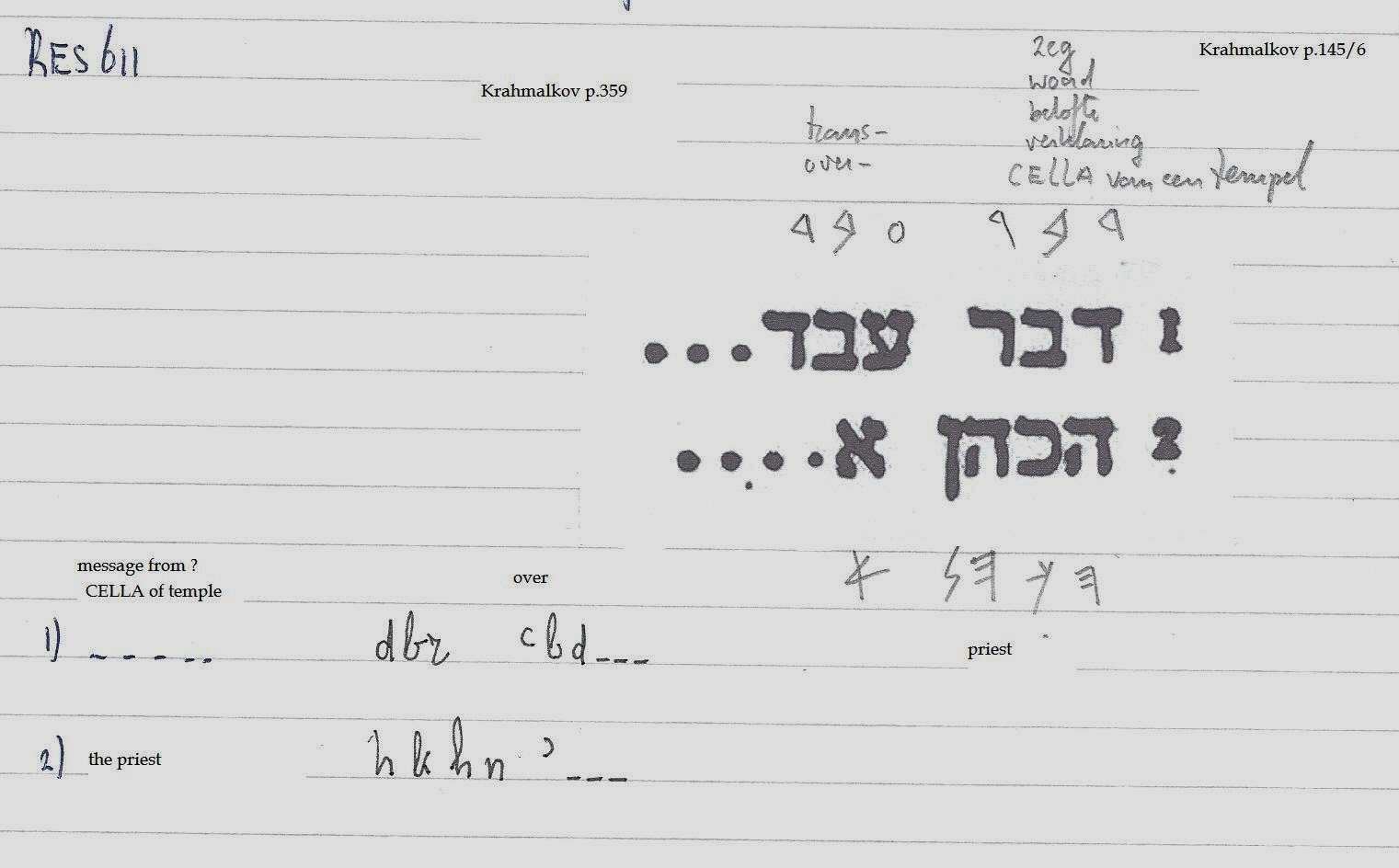

RES 611:

inscription on a block of sandstone in the necropolis along the road from Beirut to Sidon

There is

still no proof, that Han al-Hulde is also Hildua, because nothing out of the 7th

century has been found. Only the name of (k)Halde shows a great similarity to

the ancient name, which Esarhaddon in 676 BC used: hi-ul-du-u-a!

Kobbet

Choueifat.

Lipinski

continues: “More to the north, on the

slopes of the hill of Qabbat aš-šwayfet, a large Phoenician cemetery was

discovered in 1961-1962 with 422 registered tombs. The 178 tombs excavated then

by R.Saidah can be dated from the 10th through the end of the 8th

century BC. They certainly confirm the existence of an important Phoenician

town, which must be the Hildua of Esarhaddon’s inscriptions.”

There can

be no doubt that this was a Phoenician necropolis, but was it accompanied at

that spot by the town of Hildua

In this very

old cemetery the buried objects were urns for the cremation with a bichrome

painting and so-called Red Slip jars with a round mouth or a threefold mouth

and also Egyptian scarabs. Pilgrim-bottles and beer-bottles are found

especially in the oldest graves.

There is

even found a small Phoenician inscription= gtty. We don’t know what that word stands for. We

only know gṭy as a personal name.

Maybe the

name Hildua was used for both places:

Hildua-the-town

= Khaldé / Han al Hulde (no great

cemetery found yet)(only from 5th century BC)

Hildua-the-necropolis

= Aš-šwayfet (no town found yet)(from

the 7th century BC)

To make

things much more complicated: E.Forrer proposed Bet-Supuri at ‘Ayin Sawfar in:

“Die Provinzeinteilung des Assyrischen Reiches, Leipzig

Qartimme.

Somewhere

close to Beirut

Lipinski in

Itineraria Phoenicia Antioch ,

mentions a small town Khartima, which he locates in Maritime Phoenicia , at the border of Tyrian and Sidonian

territories, and considers as the birthplace of Elissa-Dido, the reputed

founder of Carthage Ch. Clermont-Ganneau identifying this with the

village of Hartum, near the source of the Nahr Abu al-Aswad (in the vicinity of

Tyrus). The place name is the same as Esarhaddon’s Qartimme, but its location

does not favour the identification of the two towns. At any rate, the name

suggests a location at the sea, possible as a marina deserving an inland city. One

may refer to the Elkardie of the crusaders, which seems to contain the element

el-Qart-, and the present-day hamlet of al-Qarteḥ, near aš-šwayfet, between

Halde and Beirut

Conclusion:

We have two towns at the coast, which use a large cemetery in the interior. Those towns are probable named hi-il-du-u-a

and qar-ti-im-me in the 7th century BC, although there are some

doubts, especially on the exact locations. The name of the cemetery also out of

the 7th century BC is not known for sure, but the location is

certain.

Literature:

ITINERARIA PHOENICIA

- Edward

Lipinski. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta nr 127. Studia Phoenicia

XVIII. Uitgeverij Peeters en Departement Oosterse Studies. Leuven – Paris –

Dudley, MA 2004.

- R.Saidah. Khan Khaldé. Dossiers de l’Archéologie 12 (1974)

p.50-59.

- M.Chébab.

Mosaïques du Liban (BMB 14-15, 1958-59.

- Nicolas

Carayon. Les ports Phéniciens et Puniques. Strassbourg 2008.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten